Here at NumisTeacher, quite often we dedicate a post to explaining basic concepts in a sort of numismatic glossary. Today, we are going to look at something that everyone has seen and held in their hands, but of which very few people know the technical name: the guilloché on a bill.

The guilloché on a banknote is a complex pattern, usually in a circular or spiral shape, composed of continuous intertwined lines that overlap each other, engraved through a mechanical process. Its purpose is to increase the security of the bill against counterfeiting.

And since a picture is worth a thousand words, I’m going to show you a close-up of the 10,000 peseta bill that was issued in Spain in 1985:

The denomination, 10,000, is superimposed on three circular designs, one on top, and two on the bottom. Those three circles are guillochés.

The origins of guilloché

Guilloché is not something new, nor is it exclusively used on bills: decorative patterns have been found in civilizations as far apart as Rome or the Andean civilizations of South America.

But modern guilloché arises with the invention, at the beginning of the 19th century, of the “rose engine lathe”, the machine that allowed for the mechanical creation of these circular patterns. And thanks to its spectacular appearance and the difficulty of reproducing it, guilloché became almost universal in the enamel of ultra-luxury decorative products.

For example, it can be seen in some Fabergé eggs from the end of the century.

And when, in the mid-19th century, the first paper documents that required special anti-counterfeiting security were issued, the rose engine lathe, and the guilloché it produces, proved to be the perfect tool to provide it.

Perhaps the best example of this is the first stamp in history, the British Penny Black of 1840, which has guilloché on the sides:

By the way, if you want to know how a rose engine lathe works, you can watch this video of a man using it to make a beautiful silver pendant:

The spirograph

Today, when we think of a spirograph, we think of one of those toys for kids that became so popular in the 1970s and 80s.

But, in reality, its original invention was the work of the British engineer Peter Hubert Desvignes, who came up with it in 1827. Not knowing what to do with it, he reinvented it in 1848, precisely to provide banknote designers with new security marks.

And it was the combination of the spirograph and the rose engine lather that makes the guilloché explode as a design element of the banknotes we use.

Guilloché in banknotes

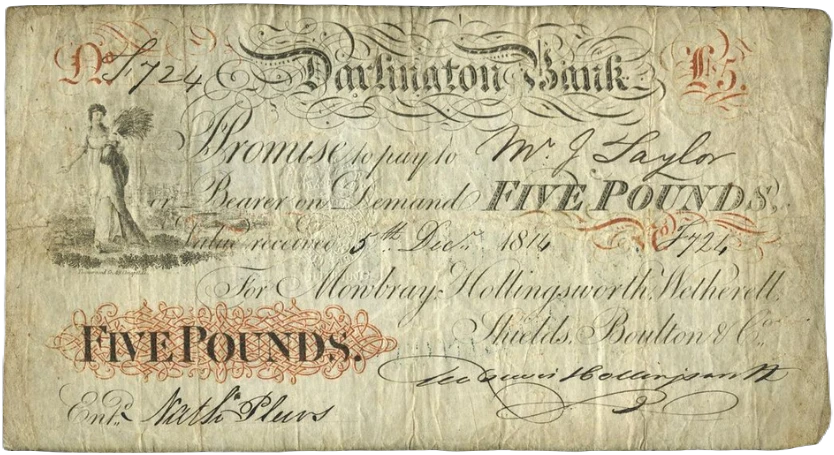

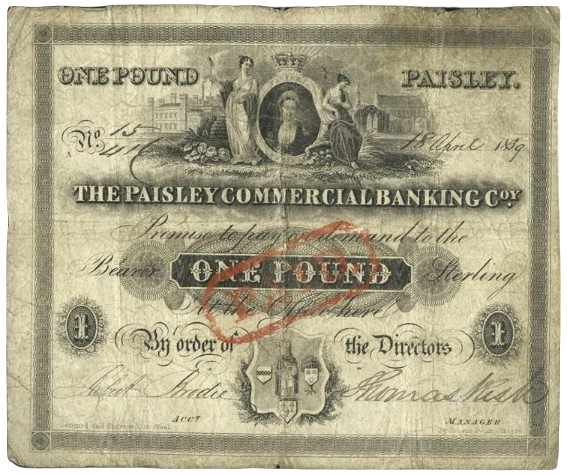

Given the potential of guilloché as a security measure, it soon jumped to banknotes. The first guillochés on banknotes were hand-made, as you can see where it says “Five Pounds” on these 5 British pounds issued in 1814 by the Darlington Bank.

But it’s precisely the invention of the rose engine lathe and its combination with the spirograph that popularizes the guilloché in paper currency, first in England, and then worldwide.

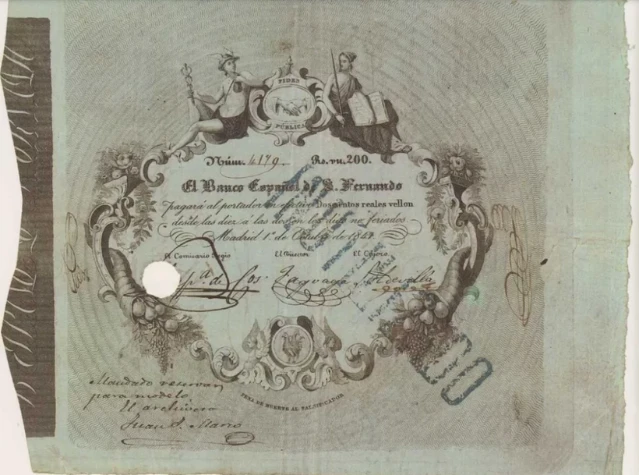

In Spain, the first banknotes with guilloché were the 200 reales of the Bank of San Fernando, issued with a date of October 1, 1847. The paper field is completely covered with guilloche:

But at that time, it seemed to have a more experimental than real use. The 200 reales note is the only one that carries guilloché.

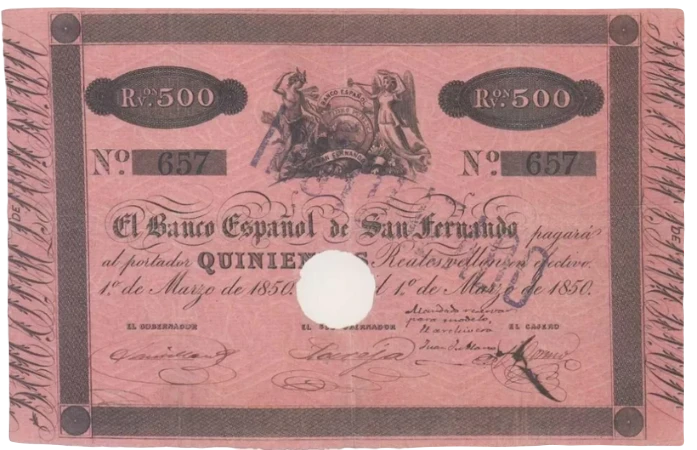

However, it looks like the experiment was a success, because, in the issue of March 1, 1850, all banknotes already have guilloché, especially in the frame that surrounds the legends. And under the face value mark, for the first time, we can find the round guilloché type that will become prevalent a few years later, and that is probably due to the invention of the spirograph.

From there, it will become one of the most ubiquitous security measures in Spanish and world banknotes.

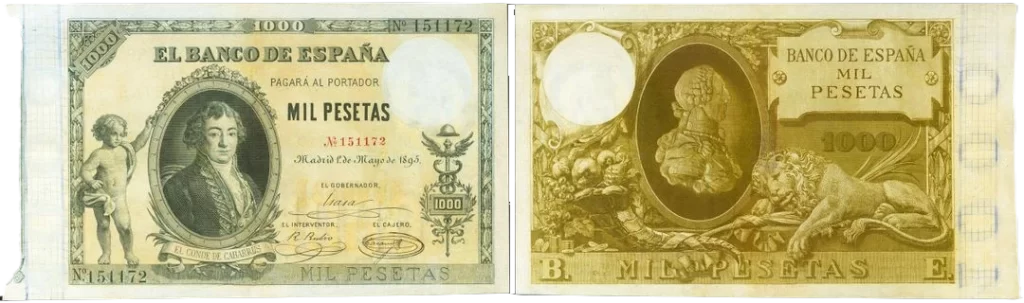

To give a few examples out of the thousands that exist, guilloché can be seen in the corners of the 1000 pesetas banknote from 1895:

In the columns on the obverse, and below the denomination of the 1000 pesetas from 1931:

Or in the background and lower corner on the obverse of the 1000 pesetas from 1992:

And that is what ‘guilloché’ is in banknotes, one of those rare elements that are simultaneously very familiar and relatively unknown. By the way, they’re also on the dollar banknotes, but they’re hidden. And that’s a story for another day.