A few weeks ago, I received a very interesting message from a Spanish reader who recently experienced a small numismatic setback from which a few lessons can be learned about bargains, counterfeits, and interactions with coin sellers.

Here is the message the reader sent me, which I reproduce with their permission and whom I will keep anonymous.

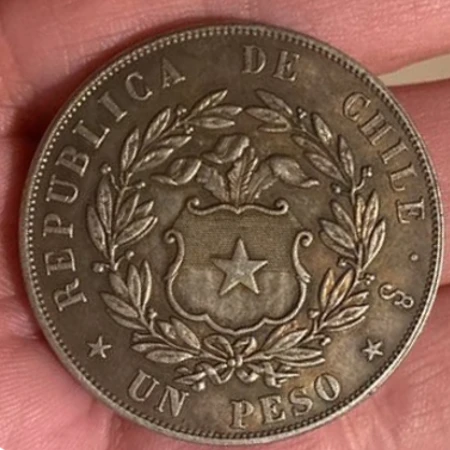

A few months ago, at a Sunday numismatic flea market in my city, while going through one of those cheap world coin boxes (where each coin was priced at €2), I found a 1 Chilean peso coin from 1862. For sentimental reasons, I felt compelled to buy it without knowing anything about it. At that price, I could afford the risk that comes with ignorance.

When I got home, I looked up information about the coin and saw that it was not only scarce but also made of silver. That, of course, made me very suspicious because the silver content alone would make it worth 14/15 euros. I checked the weight and diameter, and it matched. I tested it with a magnet, and it wasn’t magnetic. Although rationally I still suspected it was fake, I guess something inside me wanted to believe I had found a bargain. Beginner’s luck, I suppose.

Since one can’t live on hope alone and I wanted to know what I actually had, I contacted a Chilean coin shop who asked for photos of the coin. I sent them, and shortly after, they replied tersely and reluctantly that it was what it had to be: a counterfeit. They didn’t want to give me more explanations about why, at a glance in a photo, it’s clear that it’s a fake coin. I understand that it’s not their obligation to teach me anything, and perhaps they felt I was wasting their time.

Now I’ve seen the same coin being sold on AliExpress for 1.5 dollars as a reproduction.

My main question is:

Is it ethical to sell a forgery in a mixed coin box at a flea market, even at the price of the forgery, without specifying what it really is? Is it something to be expected? Should I avoid this stall at the flea market in the future? I think I should, but I’m interested in your opinion.

Counterfeits in coin boxes

I don’t know which specific seller our dear reader is talking about, but I can say that a majority of sellers who have boxes of inexpensive world coins usually don’t check them, or if they do, it’s very, very superficially.

The reason for this is a simple cost-benefit equation. Like in any other business, a coin shop has to maximize the profit it makes per hour worked.

Let’s say that cataloging a regular coin and verifying that it’s not a counterfeit takes you 5 minutes. That means, in an hour, you can process 12 coins. And let’s also say that your profit margin is 20% (this is an example, each seller will have their own margin).

If you invest that time in a coin that you’re going to sell for 2 euros, a 20% profit margin means you will earn 40 cents on that piece. With this calculation, if you look at 12 coins in an hour, your profit per hour of work will be 4.80 euros.

And a profit of 4.80 euros per hour is totally unsustainable in any business. If you do the math, you’ll see that it’s even quite below the minimum wage in many countries.

Therefore, it’s normal for a merchant to focus their limited time on more valuable coins and invest little to no time in these coin boxes. They will need to focus on pieces that yield a higher return, which brings them closer to the profit per hour goal that their business plan has set as the minimum for their store to be economically viable.

Moreover, with these calculations in hand, you might even find it normal that there are counterfeits in those cheap coin boxes. Therefore, I wouldn’t worry about it, and much less cross off the seller from my list if they sold you one from that box and it turns out to be fake (the situation changes if it’s a more significant and valuable coin, of course, but that’s a topic for another day).

Why do they put them there?

Reading this, you might be wondering why sellers bother to even have one at their stand or store if the profit from those cheap world coin boxes is so meager.

Each seller will have their particular answer to that question, but I (who am not a seller, just some guy with a blog) think there are two major intangible benefits to placing one of these boxes at your stand.

The first is to get those who are starting to collect used to buying from them.

It’s rare for someone who has been collecting for a few months to spend hundreds of euros on a coin. However, that person does have the potential to do so in the future, as their collection evolves. If that person has bought coins from you for 20 cents or 2 euros and is happy with the piece and the service you’ve provided, it’s quite possible that you’ll be one of the first options if one day they want to buy a coin for 200 or 2000 euros.

The second is to be a point of creation for new collectors.

It often happens that someone who doesn’t collect coins comes across a Sunday flea market and starts looking around out of curiosity, or just to pass the time. And who knows, maybe they don’t buy anything. Or maybe, for whatever reason, they find a coin in the 20-cent box amusing. Or maybe they go with their child, and the child likes it. So they decide to buy it, after all, it’s just 20 cents.

Perhaps the coin ends up stored in a drawer until who knows when. But it’s also possible that this 20-cent coin becomes the seed of a new collection and a new collector. And their first numismatic memory is going to be buying that coin from you. From a marketing standpoint, that’s very powerful. I perfectly remember where I bought my first coin, and to this day, I visit their website more or less regularly.

But let’s get back to the reader’s email.

The Other Three Lessons from the Reader

Equally or more interesting than the question our reader asks is the context they provide. From there, we can draw three more lessons:

Lesson 1: In numismatics, bargains rarely exist

Our reader mentions being excited to see that the coin they had bought for 2 euros could be worth much more.

Normally, if a coin is too cheap, there’s something odd about it. In fact, it’s one of the classic symptoms that indicate we might be dealing with a counterfeit coin.

It’s possible that a seller might have made a mistake in cataloging that coin and priced it much cheaper than the market value. It’s not the first time it has happened, it won’t be the last either, but it’s extremely rare.

However, what we cannot do is assume that we, collectors with very limited time to learn and research, can outsmart someone who is professionally dedicated to numismatics. Can it happen by sheer luck sometimes? Sure. Is it common? Not at all.

It’s true that our dear reader did not buy the coin because it was a bargain, but for sentimental reasons, yet they should still feel lucky: this lesson, which almost all of us receive at some point when we are numismatic rookies, only cost them 2 euros. In my case, it cost me 10. And I’ve met people who paid much, much more.

Lesson 2: Choose the moment and the question

One of the things I liked about the reader’s email is that it shows a level of reflection and self-criticism that I rarely find in those who write to me.

The reader mentions that they wrote to a Chilean numismatic to ask if the coin was genuine. The numismatist replied that it was not (reluctantly, according to the reader), but did not provide further details. And instead of getting angry with them for not answering all their questions for nothing in return, the reader realizes that “it’s not their obligation to teach me anything, and perhaps they felt I was wasting their time”.

Bravo.

Sometimes we forget that numismatic shops are also businesses. Unless they are very busy or attending to another customer, sellers usually have no problem responding to questions or doubts about the coins they have for sale.

But to ask whether this or that is fake, when you have no intention of buying anything there, is basically taking advantage of a professional’s knowledge for free, of a person whose business depends precisely on those insights. It’s the equivalent of calling your local electrician and saying… “My plug doesn’t work, how do I fix it without paying you?” Logically, the electrician will tell you to get lost.

It’s a different matter when you’ve paid for some coins. In my experience, if I’ve bought a piece from them and at the end of the transaction I think of a question about any coin, even one that they don’t have for sale, a seller will generally have no problem answering it.

Lesson 3: Ignorance comes at a cost

In numismatics, there is a maxim that comes from time immemorial: “First the book, then the coin.”

This phrase, as clichéd as it is full of truth, means that to avoid getting into sticky situations with coins, it’s better to acquire enough knowledge to know what we’re buying.

Our reader, despite making a textbook impulse purchase, seems to keep this in mind and tells us that “for that price, I could afford the risk that ignorance entails.” Good for him.

And the fact is, when it comes down to it, being sure that the coin we have is genuine comes at a price, which we have to pay in one way or another. And there are three ways to pay:

- Pay with money to experts who know more than we do and who can guarantee the authenticity of a coin.

- Pay with money for a coin without knowing anything about it, risking throwing it away if it turns out to be fake.

- Pay with time, using it to acquire enough knowledge to distinguish a fake from a good one, and, along the way, enjoy the study.

In the end, numismatics, just like life itself, is a tug of war between time and money. You decide how to balance them. I, for one, have it crystal clear.