The infamous 1933 Double Eagle gold coin has the most convoluted story in US, and probably, world numismatics. It has it all: a robbery straight out of Hollywood, a Secret Service investigation, trips to exotic places, geopolitical tension, a mysterious disappearance, and an exorbitant price.

In fact, owning one is illegal: if you happen to come across one and purchase it, you could end up in a US prison. But I doubt very, very much you will ever run into one in the wild, because the thing is… the only 1933 Double Eagle in private hands is the most expensive coin in the world.

Today, I’m going to tell you the story of this legendary coin, which has even inspired a number of fiction novels.

The Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle

Theodore Roosevelt was one of the most influential presidents in US History. He had a finger on almost everything, and that included coins. As it happens, Teddy was a fan of Ancient Greek and Rome numismatic designs, which had very high reliefs, and he disliked very much the look of the US coinage. So, in 1904, he decided it was time to make it look prettier.

Nevertheless, in order to change most of the US designs, Teddy had to ask Congress for permission. And yet, there were five coins that were exempt from congressional approval: the cent, and the four gold coins used at that moment (2.5, 5, 10 and 20 dollars). So he figured he would start with the biggest of them all: the 20$ coin, also known as the Double Eagle.

The 20$ Double Eagle was one of the coins with the highest facial value the US has ever had. This piece did circulate a bit among the population, but its true purpose was to facilitate international trade. Due to prestige reasons, it made sense for it to be the first coin to go through a redesign.

In order to carry it out, Roosevelt reached out to Augustus Saint-Gaudens, a scultptor who happened to be a close, personal friend of his, and commissioned a new design for the Double Eagle. Saint-Gaudens didn’t have much experience designing coins, but he accepted anyway. It would be the first time that someone not belonging to the US Mint designed a coin.

And what it had to happen, happened: inexperience hit. There were many delays in the delivery of the design due to the relief, too high for a coin. In fact, Saint-Gaudens, by then suffering of a late-stage cancer, wasn’t able to hand in a viable design until 1907. And, even then, it was still too high of a relief: if you take a look at the pictures below, you’ll see how, even though the coin in a pretty good conservation state, the higher elements are quite worn out.

Charles E. Barber, at that point the Chief Engraver of the US Mint, decided to reluctantly accept the design. Even though he questioned the viability of actually minting such a high relief, Barber was in the middle of designing whole new sets of coins for Cuba and the Philippines, and reached the conclusion that it would be better not to go against the president on this, or get involved in weird redesign experiments.

Thus, the production of the Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle went into trial period. And, immediately, another problem arose: if a regular coin needs just one die press to have all its details properly shown, the Saint-Gaudens piece needed nine. Nine. And made with a special machine for high relief coins. It was unsustainable.

Cancer took Saint-Gaudens before he was able to see how his work looked like on the gold planchet. But his assistant, Henry Hering, continued his work, and started to design a new version with a lower relief, but it still wasn’t low enough. So Barber, realizing that the new model was going to be implemented no matter the cost, couldn’t avoid having to get involved, and he began the process to modify yet again the design to, finally, make it viable.

Nonetheless, Roosevelt was impatient. He wanted Hering’s design to be the definitive one, and ordered for it to be immediately minted. Said and done, the US Mint manufactured a bit over 12,000 pieces of the 1907 Double Eagle, which went into circulation between 1907 and 1908.

Meanwhile, Barber kept at it, trying to produce an adaptation that was finally appropriate for mass-scale manufacture. He finished it by the end of 1907, and the pieces with his design were issued in December of that year.

Besides Roosevelt, who loved it, everybody hated the new coin. There was no “In God We Trust” motto to be seen in it (it would be incorporated later), so the public and Congress loathed it; and Barber’s modifications had been too aggressive, including the change of the numerals from the original Roman ones to Arabic ones, so Saint-Gaudens’ family despised it.

Be that as it may, the coin ended up being minted up to 1933, with a break between 1916 and 1920 due to World War I.

Gold coins? Forbidden!

And why only up to 1933? Well, another Roosevelt is at fault. This time, Theodore’s nephew in-law: the legendary Franklin Delano Roosevelt, US President between 1933 and 1945.

FDR ascended to the Presidency in the midst of the Great Depression caused by the 1929 Wall Street Crash, and his main goal was to get the country out of that economic crisis. One of his first measures was to sign the Executive Order 6102, which required US citizens to hand in to the Treasury every gold certificate, gold coin, and piece of gold bullion in exchange for its worth in paper money, with the exception of pieces with high numismatic value. Not complying would considered a felony.

This Order was in force until 1975, and it meant that any citizen who owned gold coins could get into very serious legal issues.

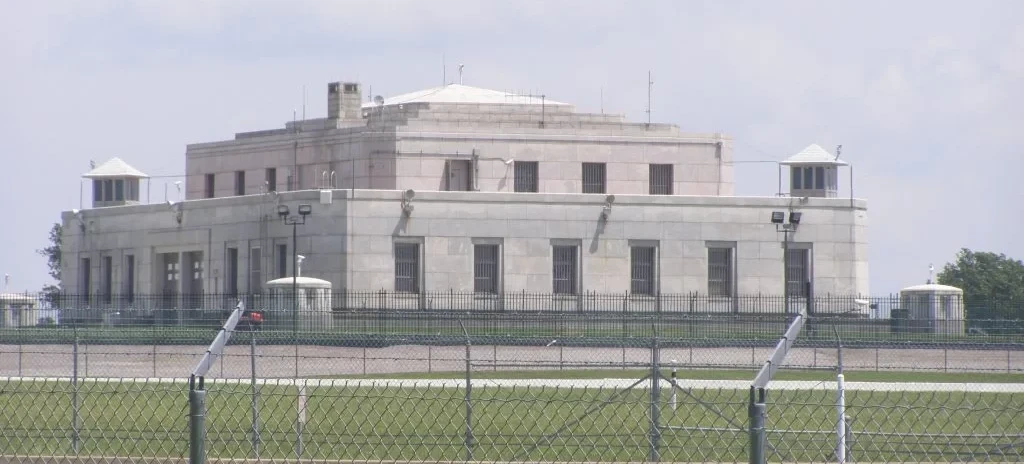

When Roosevelt signed this Order, 455,000 1933 Double Eagles had already been minted. Obviously, issuing them into circulation made no sense anymore, so they were stored in a warehouse in Fort Knox, under very close surveillance.

All of them, but two copies, were melted at the end of 1934. Those two saved from the furnace were sent to the National Numismatic Collection in the Smithsonian to be kept for posterity.

Or, at least, that’s what everyone thought.

Stack’s Bowers has one! Call the Secret Service!

At the beginning of 1944, Stack’s Bowers was organizing in their New York facilities an auction that would have been considered just another one in a long list, weren’t it for a small detail noticed by a collector who happened to be an investigative journalist.

It turns out there was a 1933 Double Eagle listed in the auction catalog. And that, theoretically, was impossible.

So this journalist reached out to some US Mint employees to try and find out what the heck was going on. And these employees, in turn, reported the finding to the US Secret Service. Besides protecting the President, the Secret Service’s mission is to investigate and prevent crimes related to physical money.

And the first thing the Secret Service did when they launched their investigation in March 1944 was to a) seize the coin, and b) talk to its consignee, who told them that he had bought it from one Israel Switt, a jeweler from Philadelphia. When questioned, Switt itself would say that he couldn’t recall who he had bought them from, but that he had sold ten 1933 Double Eagles already. This investigation ended up recovering nine coins in the period going from 1944 to 1952, which were melted.

There are several hypothesis on how Switt could get his hands on the coins. The most credible one is that a US Mint employee stole them from the warehouse. Since counting the number of coins was done through weighing a bag of coins and then dividing between the weight per coin, it is thought that this employee just swapped 1933 Double Eagles with some other, older Double Eagles, so the weight stayed the same and nobody noticed. Later on, the employee would sell them to Switt, who passed them out to wealthy collectors. Eventually, Switt would walk scot-free, as the investigation had gone past the statute of limitations and no other coin was found in his possession.

However, it is still illegal to own a 1933 Double Eagle today: besides the two pieces in the Smithsonian, all of them come from the robbery of US federal property, which is punished with prison.

But, maybe, you have noticed that while Switt sold ten coins, only nine were recovered. What about the one that’s missing?

It had to be King Farouk

As it happens, we do know what happened to the missing coin: Switt sold it to a Texas coin dealer, who sold it to a foreign buyer. And that foreign buyer was King Farouk of Egypt.

King Farouk’s story would need an article just for itself. He was a man who liked excess too much, and he made the Egyptian people pay for it. Among those excesses was coin collecting, and, in fact, he was the owner of one of the best collections in History.

Be that as it may, King Farouk wanted to do things properly this time, and he instructed the Egyptian government to ask for an export licence, which clearly said that they wanted to take a 1933 Double Eagle out of the US. And we don’t know if it was due to ignorance, apathy, or both at the same time, but the official in charge of the case granted the export request. The coin traveled from the US to Egypt on February 29th, 1944, literally just days before the Secret Service started their investigation.

Of course, as soon as they realized they had made such a huge mistake, the US government contacted its Egyptian equivalent through diplomatic channels, in order to try and get them to give the coin back. However, it was the middle of World War II and there were bigger fish to fry, so when the Egyptians refused, the US didn’t pressure them anymore.

And things just stayed like that until 1952. That year, Farouk was deposed in a coup d’état. His coin collection was put up for auction in Sotheby’s London, and that included the by now infamous 1933 Double Eagle. When the Americans heard about it, they demanded for the coin to be withdrawn from the auction and its immediate return.

The new Egyptian military government pinky-promised they would return it. But the coin disappeared.

And it wouldn’t resurface until 1996.

The most valuable coin in history

In 1996, the Secret Service got a scoop: the coin was in the United Kingdom. So they started an undercover operation with the goal of tricking the new owner, a London dealer called Stephen Fenton, into taking the coin to US soil. They were successful, and when Fenton set foot in the US, he was immediately arrested.

In the legal proceedings, Fenton argued that the coin came from the Farouk collection, and since it had an export licence, it was legal to own it. This line of defense was enough for him to be set free, but not enough to avoid a huge legal battle Fenton and the US government for the property of the coin.

The conflict wasn’t resolved until 2001, when both sides reached an agreement. The ownership would be split 50/50, the coin would be auctioned, and the government would approve a special order by which the Farouk coin -and only the Farouk coin- would be remonetized, and thus considered legal tender again.

The Farouk 1933 Double Eagle was, finally, auctioned off in Sotheby’s New York on July 22nd, 2002, and was bought by, at the time, an unknown buyer. The hammer price was 6.6 million $. Adding the 15% auction house fee, and the 20 dollars the buyer had to pay the US government to remonetize it, the final price was 7,590,020$. It was the most expensive coin in history at that point, a record that would keep until 2014, when a 1794 Flowing Hair Dollar was sold for a bit over 10 million dollars.

In 2021, the fashion designer Stuart Weitzman revealed himself as the winner of the 2002 auction when he decided to sell the 1933 Double Eagle again in Sotheby’s New York. On July 8th, it was sold for 18,872,250 $ to another anonymous buyer. Thus, the 1933 Double Eagle became, once again, the most expensive coin in history, a title that keeps up to today.

But a coin with such a story must have a coda, mustn’t it?

10 New 1933 Double Eagles

As it turns out, it does.

In 2004, one of the descendants of Israel Switt, the Philadelphia jeweler that sold off the 10 original coins back in the 40’s, found yet another ten 1933 Double Eagles in the estate of his relative. She knew the whole story, so, immediately, turned them in to the Secret Service, who took them to Fort Knox.

Once again, a legal battle ensued. There were a lot of suits, appeals, and counterappeals. However, this time, a jury decided in a 2011 trial that those 10 coins belonged to the Federal Government beyond a shadow of a doubt.

And, with this, it seems that the story is finally over. Most sources say that the number of coins stolen in the 1930’s is 20, so all of them would have been recovered. But there are other sources (granted, not as many) that say that there were 25 stolen coins, which would mean there are still 5 left to surface. Will we see a new 1933 Double Eagle someday?