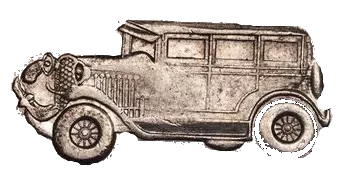

The 1928 Auto Dollar, minted in the Chinese province of Kweichow (nowadays, Guizhou) is not just one of the most iconic coins in world numismatics and the first and only coin with a car for over more than 50 years, but it also has one of the most unbelievable stories that a coin can have: it includes roads to nowhere, lethal premonitions, ambushes and Easter eggs.

Before I tell you the tale of this coin, I have to say that, even though it’s an incredibly popular coin on a worldwide scale, most of the available information is based on conjecture and in a numismatic adaptation of the Broken Telephone Game, and not much scientific-academic research has been done on it. Most probably, one of the few exceptions is the article Zhou Xicheng’s “Guizhou Auto Dollar”: Commemorating the Building of Roads for Famine Relief, by Paul Bevan. The lines you are about to read are heavily based on it.

The poorest province in China

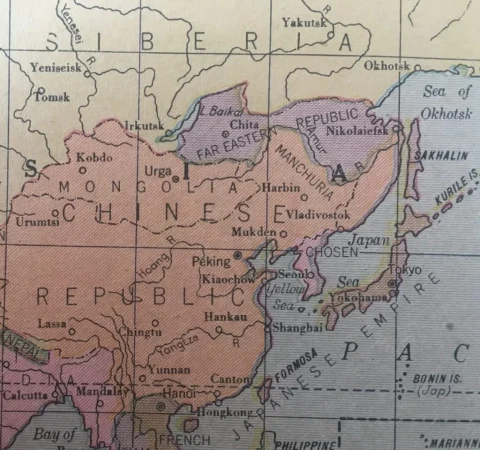

In 1912, the Qing Dynasty had been toppled in a revolution, and, with it, the Chinese Empire. The revolutionaries established the Republic of China, and, at the top of the new system, there was the so-called Beiyang Government, which was nothing more than a collective name to denote the different regimes that tried to conquer power in China between that year and 1928, when Chiang Kai-shek‘s Kuomintang managed to gain control of Nanjing (the capital of the country back then) and set a nationalist dictatorship up.

The years immediately after a revolution are always rowdy, and, as I’m sure you can imagine, those years between 1912 and 1928 were no exception. Among all that chaos, and helped by the lack of a powerful central government, starting in 1916, the Warlord Era began. A myriad of military cliques held autonomous control over certain parts of the Chinese territory, and if that wasn’t enough, Mao Zedong’s Communist Party launched an insurrection, starting a civil war that would last until 1949.

In Kweichou province, located in the center of China and today known as Guizhou, a warlord named Zhou Xicheng would seize power in 1927. Guizhou was one of those mountainous places that stood out for the magnitude of its poverty in comparison to a China that was already very poor. And, if even today it is still an area that’s quite difficult to reach, you can imagine what it was like back in the 1920’s, when there was absolutely no road or railway going into it.

Zhou Xicheng and his taste for the finer things in life

When Zhou Xicheng was officially promoted into power in Guizhou in 1927 (although he had gained effective control over it already one year earlier), the province was, for all intents and purposes, in a state of anarchy and dominated by thief gangs. And Zhou was very aware of it, as he himself had been the boss of one of those gangs before becoming a military leader.

On top of that, his personality was an explosive mix: he was an incredibly intelligent guy, but also ruthless and with no moral scruples. And that mix allowed him to enforce law and order back into the province in just two years.

But Zhou was also a guy who liked the finer things in life, and, moreover, seemed to have a fixation with American culture.

Just so you can take an example with you, I will tell you that in 1927, very soon after reaching the top provincial job, Zhou decided to buy a car. It would be the first car in a province that had no roads. He chose an 7-door American automobile, whose make and model have not been identified up to now. According to Bevan, who quotes Chinese newspapers from back then, Zhou imported the vehicle into China, ordered for it to be dismantled and for the pieces to be moved into his home by human carriers going on foot and using bamboo litters in a trip that was 50 days long, and put together again.

Don’t forget this car, it’s going to be extremely important for the rest of the story.

Guizhou didn’t have roads, but here’s Zhou… to the rescue?

Over time, Zhou reached the conclusion that the best way of keeping power would be to develop the province economically through infrastructure and education, while, at the same time, making the greatest possible effort to not awaken the rage of the Kuomintang, which had been trying to end the reach and power of the warlords already long before establishing themselves in Nanjing in 1928.

In that moment, the Kuomintang was starting a program to modernize land transportation in the country in collaboration with the Good Roads National Association of China (really, that’s its name), which today could be considered as kind of an NGO, and which was heavily inspired by the American Good Roads Movement. The reasoning behind it was that, with roads, food would be able to reach a population that was devastated by the famine that China had been going through.

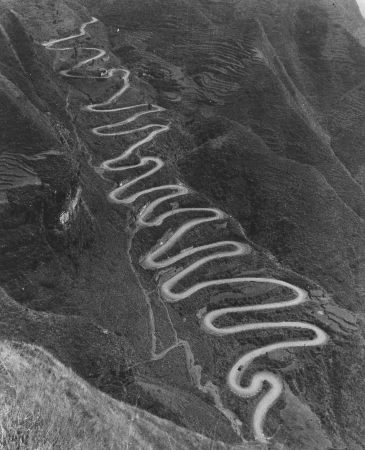

So, in 1926, Zhou started building several infrastructure projects in Guizhou, and especially, in its capital Guiyang. The star project would be the construction of the first road in the province.

The idea was a win-win-win: Guizhou would be modernized, the Kuomintang would be happy as the project was aligned with its goals, and Zhou would gain power and personal prestige, make history in the province, and have a shiny playground for his future new car.

The first road in Guizhou

In order to head the project, Zhou brought in an American engineer named Oliver Julian “O.J.” Todd, who was himself an avid collector of Chinese mirrors. Todd belonged to the International Commission for Hunger Relief in China, and was a close associate to the Good Roads Movement. And he was perfect for the job: according to Bevan, he had supervised the construction of more than 3,000 miles of roads (around 5,000 kilometers) in China, besides several projects on the control of floods caused by China’s rivers.

Bevan quotes an extract from Todd’s autobiography, published in 1939 and titled Two Decades In China, in which he describes the welcome that Zhou gave him when he arrived to Guaizhou:

“[Todd was greeted by] the governor and his full staff just outside the city in the first automobile that had ever been brought into the province. The governor appeared in white uniform with gold-ornamented sword. His whole local army of 10,000 men stood at attention. Officers saluted. No visiting potentates could have been more highly honoured. The gold braid on the uniforms of the brass band alone shone, and the strains of ‘The Red, White and Blue’ and ‘Swanee River’ filled the air.”

Plus, in that welcoming, there was an American-style military band, which was a complete novelty in China, and whose director had studied in the US by Zhou’s own orders.

The construction of the road took two full years, and it would end up being laconically named as the “Guizhou Provincial Highway”. According to Bevan, who in turn quotes Todd, manpower wasn’t a problem: Zhou ordered for the length of the road to be equally divided among the 50,000 men who lived in the province at the time, and those men would build it in the mornings before starting with their daily tasks.

Nonetheless, the road had a design flaw: it led to nowhere. It left Guiyang in a northwestern direction, but it didn’t connect with any other road in the country.

And yet, that wasn’t an impediment for Zhou to decide that the inauguration celebration would be as ostentatious as humanly possible. Also, he ordered a commemorative coin to be minted, one that would end up being an omen of his demise.

A coin with a surprise

Traditionally, since the final years of the 19th century, Chinese coins used to include dynastic or patriotic motifs, such as mythological dragons. Each province minted their own, but the size and measures were standardized for the whole of China, and any province’s coins would circulate in the whole of the country.

However, the Chinese warlords started to show their own portraits in their province’s coins as a representation of their own power. And this was something that the Kuomintang deeply loathed and frantically prosecuted, as it was a symbolic but clear challenge to their control over the Chinese territory.

Zhou, who personally took charge of the commemorative coin’s design, decided that one side of the coin would portray his car in the brand-new road, and, the other side, his portrait. His advisors didn’t show a lot of enthusiasm for the latter as they didn’t want to awaken the Party’s rage, and, after much insisting, the Governor ended up conceding to them and replacing his face with the legend ‘Guizhou Silver Coin’ in the center surrounding a flower motif, ‘Republic of China Year 17’ in the top part, and the facial value, ‘One Yuan’, in the lower part.

Zhou kept the car, though, and it is portrayed going along the road above a grass field, surrounded by the legend ‘Minted by Guizhou’s Provincial Government’ on top, and below, the silver weight of the coin in traditional Asian units, ‘7 Mace and 2 Candareens’ (0.97 ounces or 27.6 grams).

And, even though Zhou renounced to putting his face on it, he wouldn’t renounce to writing his name, in one of the very few known numismatic Easter eggs.

If you pay close attention to the grass patch in the coin, you’ll notice there are areas in which the blades have a strange placement. And that placement has to do with the Governor’s ego. If you turn the coin 90º, with the car’s front side looking upwards, the blades of grass will form two Chinese characters: xi (西) and cheng (成), Zhou’s name.

The size of the coin, 7 Mace and 2 Candareens, would of course be the largest allowed to circulate in China. It was based on the Spanish 8 reales coin, or Spanish dollar, which still had a huge influence in the Chinese coinage tradition even though centuries had passed since it had been replaced as a global currency.

Around 648,000 coins were minted. And where? That’s one of this coin’s great mysteries. We don’t know if Guizhou had its own mint, but academics do have three hypotheses on it.

The first one says that minting was outsourced to Sichuan‘s mint, on the basis of the flower ornaments splitting the coin’s legends.

The second and the third hypotheses coincide in the place, and both say that it was in Guizhou’s own capital, putting forward that, as part of the province modernization drive, Zhou ordered the construction of a mint in the city’s armory.

However, they differ on how the machinery for the mint was procured. One says that Zhou ordered his soldiers to steal it from Sichuan and bring it back to Guizhou. The other, which is the one defended by Bevan, says that Sichuan voluntarily sent machines and experts to Guizhou to help with the mint’s construction.

Zhou’s death

Today, China is still a very superstitious country. And, if it is so today, you can imagine how much more it was so back then. Mentalists and fortune tellers even took part in the system of government.

Bevan tells us that, when some fortune tellers saw Zhou’s name in the grass under the car, they immediately predicted that the coin would cause the Governor’s death. And, to be more precise, he would perish in a car-related scenario. Zhou paid no mind to the warnings, but not because he wasn’t a believer, but because those superstitions did not come from the branch he believed in.

In 1929, Zhou finally changed sides, and openly challenged the Kuomintang instead of trying to placate it. The party soon sent troops to topple him, and both sides faced each other in open battle on May 22nd of that year. Zhou commanded his soldiers from his car. It would be the last time he rode it.

Once again, my dear Bevan tells us that, in the middle of the fight, Zhou sped up, and we don’t know if on purpose or by accident, but he left his troops behind and stood alone in the vanguard of the front. There was a swamp full of reeds in the battlefield, and the car got stuck in it, slowly sinking while his foes surrounded him and prevented him from escaping. He would drown to death.

There’s another, much more beautified, version of the story that says that it wasn’t a battle at all. In this version, Zhou was driving along the road with his troops, he got separated from them, and was ambushed by a rival warlord’s soldiers, who murdered him. They left his corpse on the grass, next to his car. It would have been poetic, but, unfortunately, this tale is nothing more than a legend.

Be that as it may, the premonition had been fulfilled.

The value of a 1928 Auto Dollar

The 1928 Auto Dollar was a true hit with coin collectors almost from the moment it was issued. It was the first coin with a car, so it appealed to car enthusiasts as well as to numismatic aficionados. And, even though they circulated quite a bit, by 1933, they were already scarce in the specialized marketplace.

Furthermore, if my research does not fail me, there wasn’t any other coin with a car until the Isle of Man issued a 50 pence coin with one in 1983.

So, between its history, its design, and the fact that it’s almost impossible to find one in mint state, the 1928 Auto Dollars are expensive, sought-after coins.

A 1928 Auto Dollar in a not-so-good conservation state may have a value of 5,000$, one in a middle-of-the-pack conservation can be around 10,000$, and the best examples can go over 100,000$, such as this one that was auctioned off in 2019 for 132,000$. With these prices, I’m sure I don’t have to tell you to be careful if you intend to buy one, as there are a lot of fakes out there.